Currency

January 04, 2018

Fall-related violations continue to dominate OSHA's top 10 employer workplace safety violations. In fiscal 2016, the No. 1 violation (as it is each year) was Fall Protection—general requirements, with 6,072 violations. The No. 3 violation was scaffolding (3,288 violations); No. 6 was ladders (2,241 violations), and No. 9 was fall protection—training requirements: (1,523 violations).

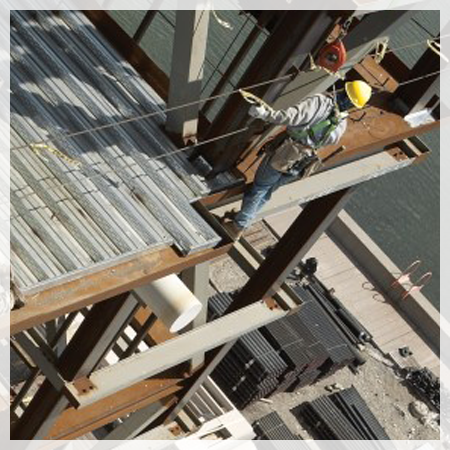

Falls continue to be among the leading causes of worker injuries and deaths. By reviewing key hazards, safety cultures, the impacts of regulations, and personal protective equipment (PPE), safety managers can encourage and support safe practices for individuals who work at height.

"Working at height" refers to work that takes place in any circumstance in which a fall could cause personal injury. This includes working on a ladder, a flat roof, or a fragile surface or even in an area near an opening in a floor or a hole in the ground. A key point for any of these situations: Workers don't need to fall far to be seriously injured or even killed.

Work at height takes place across a diverse range of industries. Many hazards may be specific to a given working environment. However, a common cause of accidents is a failure to take sufficient precautions, especially when carrying out work at relatively low heights (4 to 6 feet). Workers may fail to plan correctly and underestimate the risks involved in working at such minimal elevation. They won't secure themselves or the equipment properly, or they may place equipment in inappropriate areas where the footing isn’t secure.

A company's safety culture strongly influences the way workers behave when they work at height—and therefore affects the likelihood of accidents.

Many companies are entirely compliance-driven. They may supply workers with the correct PPE and sometimes deliver basic training, but once they meet essential legal requirements, their efforts end. Employees are furnished the equipment for the job and are expected to know how to use it correctly. Such companies believe that since they have provided the minimum that is required; if something goes wrong, the worker must be at fault.

Companies in a second category take a somewhat more progressive approach. They actively seek to reduce risks, albeit in a short-term or at most medium-term time frame. Driven by data such as key performance indicators (KPIs), these companies may take training seriously. They inspect PPE dutifully and managers attend the site, monitoring workers to make sure they are using their equipment correctly.

Yet regulatory compliance or short-term thinking alone is clearly not enough to truly ensure workers are kept safe and to avoid serious accidents with injuries or fatalities. A third category—one to which all companies should aspire—comprises employers with a strong safety culture. These organizations take a long-term approach and recognize that good safety management is a business enabler rather than a burden. In industries where the competition for skilled labor is fierce, such as oil & gas and utilities, demonstrating that a company cares about the health, safety, and well-being of workers can go a long way toward helping it retain staff. Training and supervision are taken seriously. Management regularly inspects equipment, conducts practices on site, encourages feedback from workers, and disseminates best practices. Displaying this cultural commitment helps instill positive safety behavior throughout the organization.

However, sometimes even commitment to a strong safety culture isn't quite enough. Some problems are still in an ongoing process of being solved by safety equipment manufacturers. As users identify issues, manufacturers respond with new equipment. Perceptive safety managers track these developments and make investments in new solutions when circumstances justify them.

For example, a major challenge manufacturers face is how to assess the aging of materials used in products such as safety harnesses. Specifications usually state that a harness can be used for a period of 10 years, if inspected annually. But is mere visual inspection really enough? How can a safety manager be sure that webbing is still sufficiently fall resistant, even after only two or three years, if it has been exposed to harsh conditions during that period?

n response, the PPE industry is focusing on the development of an aging detector. This should enable safety managers to determine if the resistance of a given material will still be strong enough to hold in the event of a fall.

In a related area, the industry is seeing changes in the use of self-retractable lifelines (SRLs). Until now, companies could use SRLs (for both horizontal and vertical applications), even when workers were carrying out work close to the edge of a roof. All users had to do was add a steel sling at the end of the SLR to ensure that it didn't break on the roof edge.

A new regulation, however, enforces stricter controls. This stringent new safety standard for fall arrest devices (ANSI Z359.14-2014, Class B & LE) directs manufacturers and employers to focus attention on solutions and practices that will prevent the severing of a lifeline and protect a worker in the event of a fall.

Traditional SRL designs have not addressed safeguarding workers from dangers associated with an edge. But without proper edge protection, conventional lifelines risk being compromised or severed. In fact, up to 80 percent of fall protection applications have the potential for a lifeline to come into contact with an edge during a fall. So there’s tremendous need for a safety product that can protect against this risk.

In response, manufacturers are moving to offer versatile new SRLs designs. For sharp-edge applications, these feature a durable cable lifeline. Models for smooth-edge applications are equipped with a durable web lifeline that is cut, abrasion, and chemical resistant. These new choices should provide welcome solutions for safety managers with employees working at height—and at the edge.

Working at height carries inherent hazards. Risks need to be properly assessed and work carefully planned, even at relatively low elevations. Regulation is an important driver for raising standards, but compliance alone is not enough. A mature safety culture instills positive safety behaviors, while tailor-made product solutions can provide further invaluable protection.

Falls continue to be among the leading causes of worker injuries and deaths. By reviewing key hazards, safety cultures, the impacts of regulations, and personal protective equipment (PPE), safety managers can encourage and support safe practices for individuals who work at height.

"Working at height" refers to work that takes place in any circumstance in which a fall could cause personal injury. This includes working on a ladder, a flat roof, or a fragile surface or even in an area near an opening in a floor or a hole in the ground. A key point for any of these situations: Workers don't need to fall far to be seriously injured or even killed.

Work at height takes place across a diverse range of industries. Many hazards may be specific to a given working environment. However, a common cause of accidents is a failure to take sufficient precautions, especially when carrying out work at relatively low heights (4 to 6 feet). Workers may fail to plan correctly and underestimate the risks involved in working at such minimal elevation. They won't secure themselves or the equipment properly, or they may place equipment in inappropriate areas where the footing isn’t secure.

A company's safety culture strongly influences the way workers behave when they work at height—and therefore affects the likelihood of accidents.

Many companies are entirely compliance-driven. They may supply workers with the correct PPE and sometimes deliver basic training, but once they meet essential legal requirements, their efforts end. Employees are furnished the equipment for the job and are expected to know how to use it correctly. Such companies believe that since they have provided the minimum that is required; if something goes wrong, the worker must be at fault.

Companies in a second category take a somewhat more progressive approach. They actively seek to reduce risks, albeit in a short-term or at most medium-term time frame. Driven by data such as key performance indicators (KPIs), these companies may take training seriously. They inspect PPE dutifully and managers attend the site, monitoring workers to make sure they are using their equipment correctly.

Yet regulatory compliance or short-term thinking alone is clearly not enough to truly ensure workers are kept safe and to avoid serious accidents with injuries or fatalities. A third category—one to which all companies should aspire—comprises employers with a strong safety culture. These organizations take a long-term approach and recognize that good safety management is a business enabler rather than a burden. In industries where the competition for skilled labor is fierce, such as oil & gas and utilities, demonstrating that a company cares about the health, safety, and well-being of workers can go a long way toward helping it retain staff. Training and supervision are taken seriously. Management regularly inspects equipment, conducts practices on site, encourages feedback from workers, and disseminates best practices. Displaying this cultural commitment helps instill positive safety behavior throughout the organization.

Keep an Eye on New Safety Equipment

However, sometimes even commitment to a strong safety culture isn't quite enough. Some problems are still in an ongoing process of being solved by safety equipment manufacturers. As users identify issues, manufacturers respond with new equipment. Perceptive safety managers track these developments and make investments in new solutions when circumstances justify them.

For example, a major challenge manufacturers face is how to assess the aging of materials used in products such as safety harnesses. Specifications usually state that a harness can be used for a period of 10 years, if inspected annually. But is mere visual inspection really enough? How can a safety manager be sure that webbing is still sufficiently fall resistant, even after only two or three years, if it has been exposed to harsh conditions during that period?

n response, the PPE industry is focusing on the development of an aging detector. This should enable safety managers to determine if the resistance of a given material will still be strong enough to hold in the event of a fall.

Safety at the Edge

In a related area, the industry is seeing changes in the use of self-retractable lifelines (SRLs). Until now, companies could use SRLs (for both horizontal and vertical applications), even when workers were carrying out work close to the edge of a roof. All users had to do was add a steel sling at the end of the SLR to ensure that it didn't break on the roof edge.

A new regulation, however, enforces stricter controls. This stringent new safety standard for fall arrest devices (ANSI Z359.14-2014, Class B & LE) directs manufacturers and employers to focus attention on solutions and practices that will prevent the severing of a lifeline and protect a worker in the event of a fall.

Traditional SRL designs have not addressed safeguarding workers from dangers associated with an edge. But without proper edge protection, conventional lifelines risk being compromised or severed. In fact, up to 80 percent of fall protection applications have the potential for a lifeline to come into contact with an edge during a fall. So there’s tremendous need for a safety product that can protect against this risk.

In response, manufacturers are moving to offer versatile new SRLs designs. For sharp-edge applications, these feature a durable cable lifeline. Models for smooth-edge applications are equipped with a durable web lifeline that is cut, abrasion, and chemical resistant. These new choices should provide welcome solutions for safety managers with employees working at height—and at the edge.

Working at height carries inherent hazards. Risks need to be properly assessed and work carefully planned, even at relatively low elevations. Regulation is an important driver for raising standards, but compliance alone is not enough. A mature safety culture instills positive safety behaviors, while tailor-made product solutions can provide further invaluable protection.